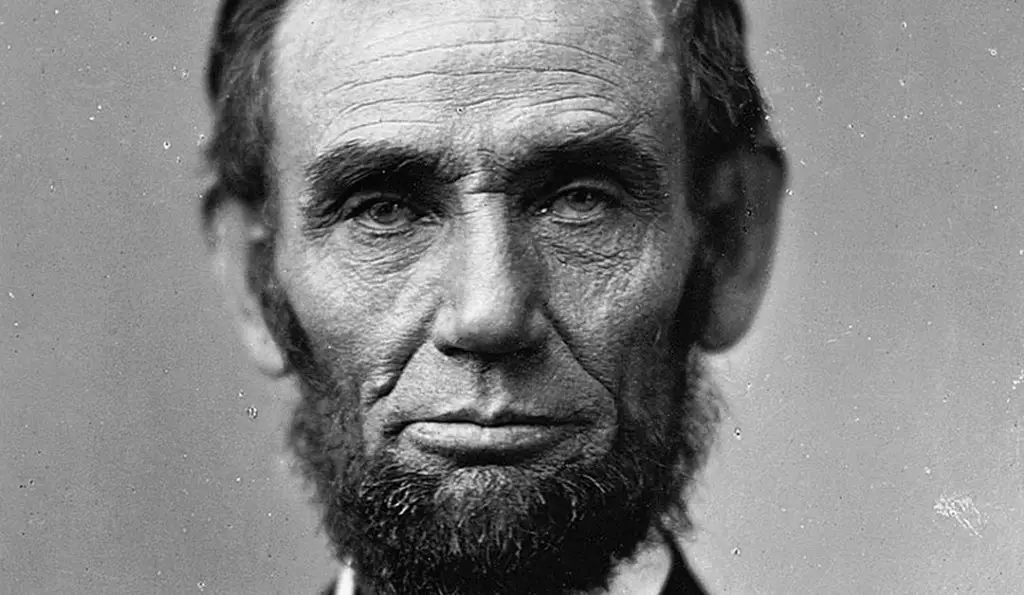

February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865

Rising from humble beginnings, Abraham Lincoln was elected as the 16th President of the United States in 1860. Lincoln’s election prompted the secession of several Southern states and eventually the beginning of the American Civil War. Lincoln served as president and commander-in-chief throughout most of the conflict before an assassin’s bullet tragically cut his life short on April 15, 1865.

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in a one-room log cabin on his family’s farm, named Sinking Spring, in Hardin County, Kentucky. Lincoln was the second child of Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks. Early in Lincoln’s life, his family enjoyed considerable prosperity, but legal problems involving land ownership prompted his family to relocate to Indiana in December 1816. Less than two years after being uprooted, Lincoln’s mother died on October 5, 1818. A little over one year later, Lincoln’s father married Sarah Bush Johnston on December 2, 1819. Lincoln enjoyed few formal educational opportunities during his youth, but his stepmother taught him how to read and encouraged him to learn on his own. The two remained close until the end of Lincoln’s life.

In March 1830, when Lincoln was a young man, his family relocated to a new farm in Illinois. Not wishing to become a farmer, Lincoln moved to New Salem, Illinois in July 1831.While living there, he engaged in several occupations, including ownership of a general store, which eventually led him into bankruptcy. In 1832, Lincoln served briefly as a captain in the Illinois militia during the Black Hawk War, but he never engaged in combat. During the same year, he ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the Illinois General Assembly. Following his loss, Lincoln served as New Salem’s postmaster and as a county surveyor. During that time, he also decided to become a lawyer and began studying the law independently. Still active in politics, voters elected Lincoln to serve in the Illinois General Assembly in 1834, and voters reelected him in 1836. As a member of the Whig Party, Lincoln supported a free-soil position, opposing both slavery and abolitionism.

In 1836, Lincoln was admitted to the Illinois bar. A year later, he moved to Springfield, Illinois and began practicing law. Voters reelected Lincoln to the Illinois General Assembly in 1838 and 1840. While living in Springfield, Lincoln met Mary Todd, daughter of a wealthy slave-holder from Lexington, Kentucky. In 1840, the couple became engaged, but the wedding, set for January 1, 1841, was cancelled as both parties became apprehensive. They later resumed their romance and were wed on November 4, 1842.

Lincoln’s career in national politics began in 1842, when Illinois voters elected him to the United States House of Representatives. While serving in Washington, Lincoln introduced a plan to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. Lincoln also voted to censure President Polk for usurpation of powers regarding the Mexican-American War in 1848–a vote that later seemed inconsistent with Lincoln’s own actions during the American Civil War.

After completing his term in Congress and not winning reelection, Lincoln returned to Springfield to practice law in 1849. He was reelected to the Illinois General Assembly in 1854, but he declined to serve because he was pursuing election by the Illinois legislature to the United States Senate. His Senate bid was unsuccessful, but he returned to try again in 1858, running against incumbent Stephen A. Douglas, author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. When Lincoln accepted the Republican nomination for the Senate seat at the state convention on June 16, 1858, he delivered his famous line that “a house divided against itself cannon stand.” Lincoln and Douglas engaged in a series of seven debates across Illinois during the late summer and fall of 1858. Although Douglas won the election in November, the debates, which focused primarily on the issue of slavery, enhanced Lincoln’s national reputation and bolstered his reputation among Republicans. On May 18, 1860, delegates to Republican National Convention held in Chicago, selected Lincoln as their party’s candidate for President of the United States In November, Lincoln received only 39.8% of the popular vote, but his 180 electoral votes were enough to defeat three other candidates, including Stephen Douglas, in a highly sectionalized election.

The Southern response to Lincoln’s election was quick and electric. On December 20, 1860, delegates to a secession convention in South Carolina voted to secede from the Union because they viewed Lincoln’s hard-line stance against the expansion of slavery as a threat to their way of life. By the time Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4, 1861, six other states had left the United States of America. Despite attempts to resolve sectional differences–most notably the Crittenden Compromise–Lincoln faced a constitutional and military crisis the day that he took office. Events rapidly spiraled toward war when South Carolina demanded that Federal soldiers evacuate its military installation at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. After weighing several options, including abandoning the fort, Lincoln chose to inform the governor of South Carolina of his intentions to resupply the fort. At 4:30 a.m. on April 12, artillery units from the newly formed army of the Confederate States of America, commanded by General P.G.T. Beauregard, began shelling Fort Sumter, touching off the American Civil War.

Lincoln’s response was swift and somewhat autocratic, especially in light of his earlier criticisms of Polk. On April 15, without authority from Congress, Lincoln called on all state governors to send troops for the formation of a temporary force of 75,000 soldiers. That action had the unfortunate result of forcing states to choose sides, causing Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee to join the Confederacy. Further, Lincoln proclaimed a blockade against Southern ports on April 19, 1861. In perhaps his most controversial move, Lincoln suspended the constitutionally guaranteed writ of habeas corpus on April 27, 1861. When Chief Justice Roger Taney, sitting as a federal circuit judge in the case of Ex parte Merryman, ruled that Lincoln had no constitutional authority to do so, the President simply ignored the Chief Justice’s ruling. Over the course of the next two years the Lincoln administration and the Army imprisoned nearly 18,000 American citizens without bringing charges against them. Congress finally ended the controversy, but not the practice, by passing the Habeas Corpus Act of 1863, which temporarily legitimized the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus.

Lincoln’s record as commander-in-chief was also plagued with controversy. Despite having far more men and materials at their disposal, Union armies had little success during the early part of the war. A seemingly endless parade of commanders including, Winfield Scott, Irvin McDowell, George McClellan, Henry Halleck, John Pope, Ambrose Burnside, and Joseph Hooker, had limited success against their Southern counterparts. Until George Meade’s victory at Gettysburg in 1863, the performance of Union armies in the East was inferior to that of the Confederate armies. How much of the failure was a result of poor generalship as opposed to a poor choice of generals is debatable. In any case, it was not until the emergence of Ohioans Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman that Union fortunes improved.

Lincoln’s political performance as President during the war was stellar. When support for the war began to wane as battlefield casualties mounted, he gradually shifted the focus of the war to the issue of slavery. On April 16, 1862 he signed an act abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln used his war powers to issue an executive order abolishing slavery in the states at war with the Union. The Emancipation Proclamation galvanized and reinvigorated Lincoln’s abolitionist supporters, transforming the war from an effort to preserve the Union to a higher moral cause. Despite continually increasing casualty totals, public unrest elicited by the practice of conscription, and mounting criticism from Copperheads and the Northern press, Lincoln was able to sustain his political base and win reelection in 1864–no small political feat.

Even before Lincoln won reelection, he began formulating his reconstruction policy to heal the nation’s wounds when the war ended. It is perhaps in this arena where Lincoln’s star shown brightest. On December 8, 1863, Lincoln announced his plan for reunification of the nation, known as the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction. The plan advocated a full pardon and the restoration of property to all engaged in the rebellion, with the exception of the highest Confederate officials and military leaders. It also enabled states to form new governments and be readmitted to the Union when ten percent of the eligible voters had taken an oath of allegiance to the United States. Finally, the plan encouraged readmitted southern states to enact plans to deal with the freed slaves so long as their freedom was not compromised. Unlike others in his administration and in Congress, Lincoln believed that a lenient approach would best help heal the nation’s wounds once the fighting ended. When Congress tried to impose much harsher terms on the South through enactment of the Wade-Davis Bill in July 1864, Lincoln used the pocket veto to thwart his opponents. During his second inaugural address, presented on March 4, 1865, Lincoln eloquently expressed his desire “to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Whether Lincoln could have consummated his vision of “malice toward none, with charity for all” will forever remain unknown. On April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth fired a bullet into the back of Lincoln’s head as the President attended a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington. Abraham Lincoln died at 7:22 a.m. the next morning.

Lincoln’s body lay in state in the White House for dignitaries on April 18. His funeral was held shortly after noon in the White House on April 19. The next day, the President’s casket lay in state at the Capitol, where an estimated 25,000 visitors paid their last respects. On April 21, a train carrying Lincoln’s coffin, along with the body of his son Tad, who had died during Lincoln’s presidency, began the long trip back to Springfield, Illinois. The train’s route, which passed through hundreds of communities and seven states replicated, in reverse, Lincoln’s trip to Washington as the president-elect. The coffin was removed from the train to lay in state at ten locations during the trip. Abraham Lincoln was buried at Oak Ridge Cemetery, near Springfield, Illinois on May 4, 1865. Since that time, Lincoln’s body has been exhumed and reburied numerous times. Lincoln’s Tomb, in Oak Ridge Cemetery, has been the final resting place for Lincoln since 1901.

Related Entries

- George Gordon Meade

- Joseph Hooker

- Kansas-Nebraska Act

- Crittenden Compromise

- John Pope

- Battle of Fort Sumter

- Winfield Scott

- General Orders, No. 104 (U.S. War Department)

- General Orders, No. 109 (U.S. War Department)

- General Orders, No. 66 (U.S. War Department)

- President’s War Order No. 2 (Reorganizing the Army of the Potomac)

- President’s War Order No. 3

- Mexican-American War

- Stephen Arnold Douglas