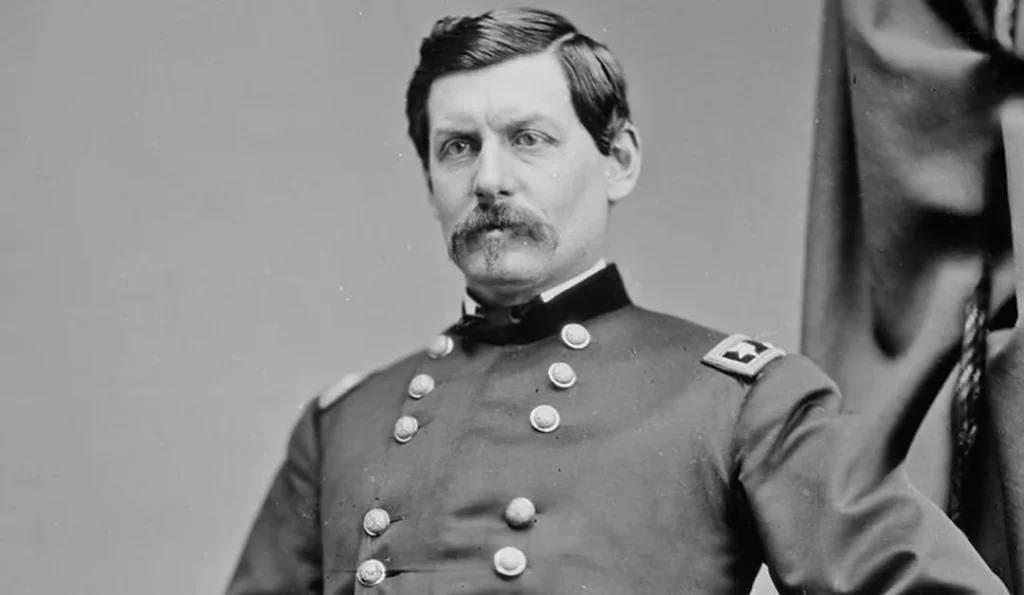

December 3, 1826–October 29, 1885

During the American Civil War, George Brinton McClellan twice served as the commanding general of the Army of the Potomac and briefly as the general-in-chief of all Union armies.

Early Life and Education

George Brinton McClellan was born on December 3, 1826, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was the third of five children born to Dr. George McClellan and Elizabeth Sophia (Brinton) McClellan. Dr. McClellan was a prominent physician and a founder of Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia.

As a precocious child from an affluent family, McClellan attended private schools in Philadelphia. At the age of thirteen, he enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania to study law. Two years later, young McClellan resolved to become a military officer. Benefiting from his father’s influence, at age fifteen McClellan received an appointment to the United States Military Academy in 1842, despite being a few months shy of the academy’s enrollment requirements.

Despite his tender age, McClellan was an outstanding student, graduating second in his class of fifty-nine cadets in 1846. During his years at West Point, McClellan rubbed shoulders with future Civil War allies and adversaries including generals Ulysses S. Grant, William F. “Baldy” Smith, Ambrose E. Burnside, John Buford, Darius N. Couch, and George Stoneman (USA), as well as Simon B. Buckner, Edmund Kirby Smith, George E. Pickett, and Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson (CSA).

Army Officer

Following his graduation, McClellan received a brevet promotion to second lieutenant on July 1, 1846, and was assigned to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. When General Winfield Scott’s Army of Invasion descended on Central Mexico in 1847 during the Mexican-American War, McClellan performed invaluable service as a combat engineer with the Company of Sappers, Miners, and Pontooners, constructing roads, bridges, and combat fortifications. During the war, McClellan was promoted to the full rank of second lieutenant on April 24, 1847. The War Department also brevetted him to the rank of first lieutenant, effective August 20, 1847, for “Gallant and Meritorious Conduct in the Battles of Contreras and Churubusco,” and to captain, effective September 13, 1847, for “Gallant and Meritorious Conduct in the Battle of Chapultepec.”

At the conclusion of the Mexican-American War, McClellan returned to West Point as an instructor with the Corps of Engineers. For the next few years he worked on numerous engineering projects for the army, primarily in the West. He also traveled to Europe on assignment as an official observer of the European armies during the Crimean War in 1855.

Railroad Engineer and Executive

Despite being promoted to first lieutenant (effective July 1, 1853) and captain (effective March 3, 1855), McClellan chafed at peacetime garrison duty.Consequently, he resigned his commission on January 16, 1857 to accept a more lucrative position as chief engineer of the Illinois Central Railroad. Within a year, McClellan had risen to the position of vice president of the company.

Now a wealthy man, McClellan renewed his courtship of Ellen Mary Marcy, the daughter of one of his former army commanders. The two had met in 1855 but had drifted apart after she rejected an earlier marriage proposal. They were reunited when her family briefly stayed at McClellan’s Chicago residence in 1859 on their way to Minnesota. This time Ellen was more receptive to McClellan’s advances. In late October, she accepted his second marriage proposal. The couple wed on May 22, 1860, at the Calvary Church in New York City. Their twenty-five-year marriage, which lasted until McClellan’s death in 1885, produced one son and one daughter.

In August 1860, McClellan accepted an offer to become president of the eastern division of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad, headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio. Less than a year later, on April 12, 1861, artillery units from the newly formed army of the Confederate States of America began shelling Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor, touching off the American Civil War. Three days later, newly inaugurated President Abraham Lincoln called on all state governors to raise troops for the formation of a temporary force of 75,000 soldiers. McClellan’s services were suddenly in high demand. The governors of three states, New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, offered him command of their state militias. Ohio Governor William Dennison prevailed and on April 23, 1861, he appointed McClellan as commander of the Ohio Militia with a rank of major general in the volunteer army.

Return to the Army

The rapid buildup of local regiments required the United States War Department to create structure out of chaos. On May 3, 1861, Washington officials issued General Orders, Number 14, placing McClellan in command of a freshly-created military unit known as the Department of the Ohio. Headquartered in Cincinnati, the new department consolidated regiments from the states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. McClellan assumed command of the department on May 13, 1861. The next day, President Lincoln informed McClellan that he was nominating him for a commission in the regular army at the rank of major general, effective May 14, 1861. McClellan accepted the appointment on May 21 and the Senate confirmed his nomination on August 3. When McClellan officially signed his commission on September 9, 1861, only General-in-Chief Winfield Scott outranked him.

Western Virginia Campaign

McClellan’s first priority after assuming command of the Department of the Ohio was organizing his command, which he accomplished effectively. By June 1861, he was prepared to mount an offensive in western Virginia. McClellan’s soldiers pressed the Confederate forces in the area throughout the summer. His victory at the Battle of Philippi on June 3, 1861, is generally considered as the first significant land engagement in the eastern theater of the American Civil War. The Union victory at the Battle of Rich Mountain on July 11, 1861, was instrumental in securing Federal control of western Virginia and the eventual establishment of the State of West Virginia on June 20, 1863.

Department and Army of the Potomac Commander

McClellan was not around to personally see the product of his successful campaign. Following the victory at Rich Mountain, President Lincoln summoned McClellan to the White House and offered him a new command. On July 25, 1861, the War Department issued General Orders, No. 47, announcing that McClellan was assigned command of the Military Division of the Potomac. On August 20, McClellan issued General Orders, No. 1, assuming “command of the Army of the Potomac, comprising the troops serving in the former departments of Washington and Northeastern Virginia, in the Valley of the Shenandoah, and in the States of Maryland and Delaware.”

Upon accepting his new appointment, McClellan set about erecting a network of nearly fifty fortifications to protect the nation’s capital. Well aware that his army consisted primarily of untrained volunteers, McClellan took his time molding the Army of the Potomac into a disciplined fighting force. By November, his well-trained legion of 168,000 soldiers represented the largest and best-equipped army the United States had ever mobilized. Despite, or perhaps because of his accomplishments, however, his list of detractors expanded and became more vocal.

McClellan’s most immediate antagonist was his direct superior, General-in-Chief Winfield Scott. Their antipathy began when McClellan scorned Hancock’s Anaconda Plan to slowly strangle the Confederacy into submission. McClellan instead favored a grand assault on Richmond. President Lincoln preferred McClellan’s strategy because it promised a quick end to the rebellion. Thus, he “encouraged” the seventy-five-year-old Scott to retire. On November 1, 1861, the War Department issued General Orders, No. 94, announcing Scott’s retirement and President Lincoln’s executive order proclaiming that “Major-General George B. McClellan . . . [would] assume the command of the Army of the United States.”

McClellan also had enemies in Congress. Some Republicans distrusted McClellan because he was a member of the Democratic Party. Radical Republicans questioned his allegiance to their mission for emancipation. Like Lincoln at the time of his election, McClellan viewed slavery as a constitutionally-sanctioned institution entitled to federal protection.

The most notable person on McClellan’s list of critics was President Lincoln. Despite his early infatuation and support for McClellan, Lincoln eventually tired of the general’s insolence and indecisiveness. McClellan formed a low opinion of Lincoln when the future president worked as a lawyer for the Illinois Central Railroad. Privately, the general referred to Lincoln as a “gorilla,” a “baboon,” and “unworthy of … his high position.” Less than two weeks after Lincoln elevated him to commander of the U.S. Army, McClellan dishonored the president when Lincoln visited his home. After compelling the president to wait for thirty minutes, McClellan sent word that he had already retired for the evening and refused to see him.

The affable Lincoln may have been willing to tolerate McClellan’s personal disdain if his general-in-chief had been willing to demonstrate that he was making progress toward bringing the rebellion to the swift conclusion that the president desired. When McClellan refused to share plans for his grand assault on Richmond, Lincoln began acting as his own general, convening private war councils with McClellan’s subordinates and making plans of his own. At one such conclave, Lincoln reportedly stated that “If General McClellan does not want to use the Army, I would like to borrow it for a time, provided I could see how it could be made to do something.” By the spring of 1862, Lincoln’s patience was exhausted. On March 11, Lincoln issued “President’s War Order, No. 3” relieving McClellan of all commands except the Department of the Potomac.

Peninsula Campaign

One week after being sacked as general-in-chief, McClellan launched his long-awaited advance on Richmond. After nearly nine months of preparation, McClellan transported the Army of the Potomac by ship to Fort Monroe, Virginia. With the majority of Rebel forces encamped near Manassas, McClellan planned to march his army up the Virginia Peninsula and to capture the Confederate capital. Although he enjoyed a numerical advantage of nearly three-to-one, McClellan advanced cautiously towards Richmond. His sluggishness provided General Joseph Johnston with ample time to reinforce the Rebel troops at Richmond. Still, the Army of the Potomac fought its way up the Peninsula to within sight of Richmond by May. The campaign stalled, however, when General Robert E. Lee assumed command of the forces guarding Richmond after Johnston was seriously wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines (May 31-June 1, 1862). Lee went on the offensive, launching a series of engagements known as the Seven Days Battles that eventually drove the Army of the Potomac back to the sea, bringing to an end McClellan’s unsuccessful Peninsula Campaign.

Northern Virginia Campaign

As the Army of the Potomac retreated down the Virginia Peninsula, President Lincoln appointed Major General Henry W. Halleck as General-in-Chief of the Army, effective July 23, 1862. Apprehensive about protecting the nation’s capital during McClellan’s absence, Lincoln and Halleck appointed Major General John Pope to command the newly created Army of Virginia in the Washington area. Sensing that McClellan now posed little threat to Richmond, Confederate General Robert E. Lee decided to take the offensive before Pope’s army could be united with McClellan’s retreating forces. In response to Lee’s impending threat, Halleck recalled the Army of the Potomac to the Washington area on August 3, 1862, and redeployed many of McClellan’s soldiers to Pope’s forces.

In late August, General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia scored a major victory at the Battle of Bull Run II (August 28 – 30, 1862). Fortunately for Pope, reinforcements from McClellan’s army approaching the battle site from Washington prevented the retreat from deteriorating into a disorganized rout similar to the one incited a year earlier on the same battlefield at the Battle of Bull Run I.

On September 7, 1862, one week after Lee’s victory, the War Department issued General Orders, No. 128, reassigning Pope to command the Department of the Northwest, headquartered in St. Paul, Minnesota. A few days after Pope was exiled into oblivion, the War Department issued General Orders, No. 129, on September 12, ending the existence of the Army of Virginia by merging its three corps with the Army of the Potomac. McClellan’s career, if not his reputation, had been resurrected. The move was immensely popular with McClellan’s soldiers who by now were fondly referring to him as “Little Mac.”

Maryland Campaign and the Battle of Antietam

After his victory at the Battle of Bull Run II, Robert E. Lee marched the Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland. On September 4, Lee’s soldiers began crossing the Potomac River near Poolesville, Maryland. Assuming that the Federal forces near Washington were still in disarray following their stinging defeat at Bull Run, Lee believed that it was safe to temporarily divide his army. The pivotal engagement of the Maryland Campaign occurred roughly two weeks later near Sharpsburg, Maryland, along Antietam Creek.

On September 17, 1862, McClellan attacked Lee. During the course of the day, Lee’s divided army reunited on the battlefield and was able to fight the Army of the Potomac to a standoff. The Battle of Antietam ended as a tactical draw, but it was a strategic Union victory because McClellan halted Lee’s northern advance. The engagement was the bloodiest single-day of combat during the American Civil War. Following a day of truce, during which both sides recovered and exchanged their wounded and dead, Lee began moving his army back across the Potomac River, but McClellan failed to press the issue.

Loss of Command

An exasperated President Lincoln urged McClellan to pursue Lee’s army while it was in disarray, but Little Mac demurred, arguing that his soldiers needed rest. In October, Lincoln visited McClellan in the field and again beseeched the general to advance and strike Lee. Even written orders from Halleck and the president could not get McClellan to budge.

There is some evidence to support the possibility that McClellan’s dilatory behavior was motivated by political rather than military rationale. President Lincoln’s use of the strategic Union victory at the Battle of Antietam as the impetus for issuing the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation displeased McClellan. Like many Northerners, McClellan believed that the war was not – nor should it be – about ending slavery. Writing to his wife on September 25, 1862, the general vented his frustrations with the document, stating “The Presdt’s late Proclamation . . . render(s) it almost impossible for me to retain my commission & self respect at the same time.I cannot make up my mind to fight for such an accursed doctrine as that of a servile insurrection – it is too infamous.”

Whatever McClellan’s motivations were, by early November Lincoln had decided that Little Mac had to go because, in the president’s homespun vernacular, he suffered from “the slows.” Not wanting to upset the applecart by sacking the leading Democratic general before the upcoming midterm Congressional elections, Lincoln bided his time. On November 5, 1862, the day after the elections, Lincoln issued an executive order relieving McClellan of his command and replacing him with Major General Ambrose E. Burnside.

Subsequently, the War Department ordered McClellan to report to Trenton, New Jersey, to await orders. Despite calls for Little Mac’s return after decisive Confederate victories over the Army of the Potomac at Fredericksburg (December 11–15, 1862) and Chancellorsville (April 30 – May 6, 1863), the War Department left McClellan in limbo.

Presidential Candidate

During his hiatus, McClellan became more actively involved in Democratic politics. When the Democrats held their national convention in Chicago from August 29 – 31, 1864, they nominated McClellan as their presidential candidate on the first ballot. McClellan’s views, however, were out of sync with the party’s platform, which was drafted by Peace Democrats. As a War Democrat, McClellan favored continuing the war until the rebellion was suppressed. The Peace Democrats, led by Clement Vallandigham, favored negotiating with the Confederacy to end the war immediately. With the party divided so distinctly, McClellan had little chance to unseat Lincoln. His prospects were further diminished when William T. Sherman’s string of battlefield victories in Georgia, which led to the fall of Atlanta in early September, rejuvenated public support for the war in the North. When the votes were tallied in November, Lincoln swamped McClellan, 2,213,665 – 1,805,237. The Electoral College results were even more lopsided with Lincoln receiving 212 votes compared to McClellan’s twelve.

Following his election loss, McClellan resigned his military commission on November 8, 1864, and returned to private life. For the next decade, he sandwiched several engineering appointments between two extensive European trips with his family. In 1877, New Jersey voters elected McClellan to the office of governor. He served one term in that capacity from January 15, 1878, to January 18, 1881. Afterwards, he spent the next four years traveling and drafting his memoirs.

Death and Burial

On the evening of October 28, 1885, McClellan suffered a heart attack at his home in West Orange, New Jersey. His condition worsened throughout the night until he passed at 2:50 a.m. the next morning. Following a public funeral at Madison Square Presbyterian Church on Monday, November 1, 1885, the fifty-eight-year-old general was laid to rest at Riverview Cemetery, Trenton, New Jersey.

Related Entries

- Ambrose Everett Burnside

- Irvin McDowell

- Battle of Antietam

- Battle of Seven Pines

- Peninsula Campaign

- Edwin McMasters Stanton

- Robert Edward Lee

- Jefferson Finis Davis

- Battle of Rich Mountain

- Ambrose Powell Hill

- John Pope

- Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

- Emancipation Proclamation

- General Orders, No. 94 (U.S. War Department)

- Army of the Potomac (USA)

- Army of Virginia

- President Lincoln’s Executive Order Relieving General G. B. McClellan and Making Other Changes

- General Orders, No. 122 (U.S. War Department)

- General Orders, No. 182 (U.S. War Department)

- General Orders, No. 282 (U.S. War Department)

- President’s War Order No. 3

- Mexican-American War

- Army of Northern Virginia

- General Orders, No. 1 (Army of the Potomac)

- General Orders, No. 15 (Headquarters of the Army)

- General Orders, No. 1 (Division of the Potomac)

- General Orders, No. 19 (Headquarters of the Army)