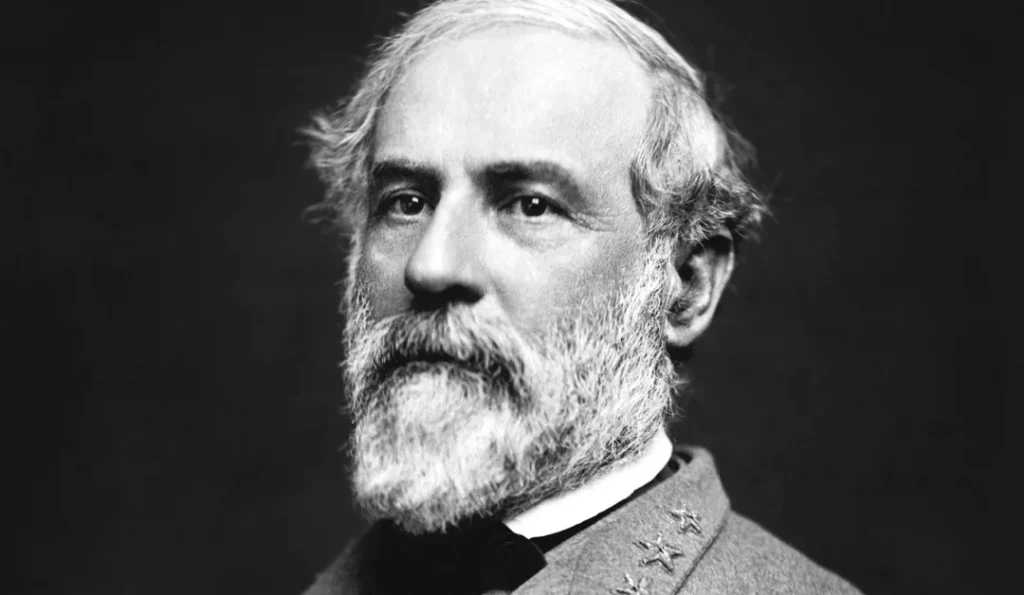

January 19, 1807–October 12, 1870

Robert E. Lee was a prominent Confederate army officer who commanded the Army of Northern Virginia throughout most of the Civil War and who also served as General-in-Chief of Confederate forces near the end of the conflict.

Robert Edward Lee was born January 19, 1807, at Stratford, a family plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He was the fifth child of Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee and Ann Hill Carter Lee.

Lee’s father was a Revolutionary War hero, a delegate to the Continental Congress, the Governor of Virginia from 1791 to 1794, and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Despite his military and political renown, the elder Lee was ruined financially by the Panic of 1796-1797 and spent a year in debtor’s prison in 1809. After his release, Lee moved his family to Alexandria, Virginia. While living there, Robert attended local schools.

In 1812, Lee’s father traveled to the West Indies and never returned, dying there in 1818. Lee’s mother was left to raise the family with the help of relatives.

In 1824, Lee’s uncle, William Henry Fitzhugh, secured an appointment for Lee to the United States Military Academy. Lee entered the academy in 1825, graduating second in his class in 1829.

After graduation, Lee was commissioned as a brevet second lieutenant in the Army Corps of Engineers.

When Lee returned home while awaiting assignment, his mother died on July 26, 1829. While at home, Lee also began courting Mary Custis, great-granddaughter of Martha Washington.

In August, Lee was ordered to Georgia. When he was home on leave a year later, Mary accepted Lee’s second marriage proposal, and the two were wed on June 30, 1831.

Also in 1831, Lee was transferred to Fort Monroe in Virginia. For the next fifteen years, Lee was away from his family, performing various engineering duties for the army, including helping to establish the state line between Ohio and Michigan in 1835. During the period, he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant in 1832, then to first lieutenant in 1836, and finally to captain in 1838.

During the Mexican-American War (1846 to 1848), Lee first served as an engineer under General John Wool, primarily laying out transportation routes.

In 1847, he transferred to the staff of General Winfield Scott, who later stated that Lee was “the greatest soldier I ever saw in the field.” Lee served with distinction at the battles of Vera Cruz (March 1847), Cerro Gordo (April 1847), and Chapultepec (September 1847), where he was wounded. Lee was promoted to brevet major after the Battle of Cerro Gordo on April 18, 1847.

After the Mexican-American War, Lee resumed his peacetime engineering duties with the army. In 1852, U.S. Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, appointed him superintendent of the United States Military Academy, where he served until 1855.

In March 1855, Lee was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given command of the recently formed 2nd U.S. Cavalry in Texas. His unit’s primary objective was to subdue the Comanche Indians.

While serving in Texas, Lee’s father-in-law, George Washington Custis, died in 1857, and Lee returned to Alexandria, Virginia to serve as executor of the estate.

Custis’s will stipulated that his slaves be freed within five years of his death. The slaves erroneously believed that they were freed at the time of Custis’s death. Lee disagreed, and when some of the slaves attempted to escape, Lee began hiring them out, in some cases breaking up families.

Lee also filed legal petitions to keep Custis’s chattel enslaved indefinitely. Only when the courts denied his petitions did Lee consent to his father-in-law’s wishes and free his slaves.

In October 1859, President James Buchanan ordered Lee to lead a detachment of U.S. Marines to Harpers Ferry, Virginia to suppress a raid on the federal arsenal led by Ohioan and abolitionist John Brown.

On October 18, after failed negotiations with Brown, Lee ordered his marines to storm the building where the insurrectionists were sequestered. In a matter of minutes, Brown and the situation was diffused. Later that year, Lee stood guard at Brown’s execution on December 2, 1859.

When the session crisis escalated after Abraham Lincoln’s election to the U.S. Presidency in 1860, Lee was torn between his sworn duty to the army and his country versus his allegiance to his home state of Virginia.

Serving as the acting head of the Department of Texas during the winter of 1860, Lee refused to cede federal property to local secessionists. In March of the following year, Lee was recalled to Washington and promoted to full colonel.

On April 17, 1861 Virginia seceded from the Union. The next day Lee declined a promotion to major general in the army being assembled to suppress the Southern insurrection. On April 20, he resigned his commission in the U.S. Army. Three days later Lee accepted command of Virginia’s forces.

The first year of the Civil War was not kind to Lee or his reputation. In an uncoordinated attack hampered by rain, fog, and mountainous terrain, Lee’s forces were defeated at the Battle of Cheat Mountain (September 12 to 15) in western Virginia.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis relieved Lee of his field command and sent him east to supervise the construction of coastal defenses in Georgia and the Carolinas.

Davis then recalled Lee to Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital, where he served as a military advisor to the Confederate president. While acting in that capacity, Lee set the army to dig a series of defensive trenches around the Confederate capital. That operation earned him the derogatory sobriquet, “King of Spades.”

The spring of 1862 marked a change in Lee’s military fortunes. By late May, Major General George McClellan had advanced the Federal Army of the Potomac to the outskirts of Richmond during his Peninsula Campaign.

On June 1, General Joseph E. Johnston was severely wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines, and Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia. As McClellan planned for a siege of Richmond, Lee prepared to take the initiative. On June 25, he launched the first of six assaults on Federal troops in seven days, collectively known as the Seven Days Battles (June 25 to July 1, 1862).

Although the Battle of Gaines Mills was the only engagement in the series that produced a tactical Confederate victory, the offensive achieved Lee’s strategic objective of driving McClellan away from Richmond.

The Army of the Potomac retreated down the peninsula until U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and General-in-Chief-of-the-Army Henry Halleck recalled it on August 3, to support Major General Pope’s Army of Virginia operating near Washington. With McClellan’s army off of the peninsula, Lee turned his attention to Pope and scored a major victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 28 to 30, 1862), opening the way for a Confederate invasion of the North.

In September 1862, Lee moved the Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland. His Maryland Offensive had three major goals: relieve Virginia from the ravages of war, resupply his army through foraging in the North, and erode Northern morale enough to influence upcoming midterm elections in the North.

McClellan dispatched the Army of the Potomac to Maryland to check Lee’s advance. The two armies met at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland. During the bloodiest day of fighting in the Civil War, the armies fought to a standoff. With his advance stalled and supplies running low, Lee withdrew to Virginia.

Disappointed with McClellan’s failure to pursue Lee’s retreating army, President Lincoln placed Ambrose Burnside in command of the Army of the Potomac on November 7, 1862, and urged him to mount an offensive. A reluctant Burnside crossed the Rappahannock River on December 12. The next day he ordered a disastrous series of frontal attacks against Lee’s well-positioned army near Fredericksburg, Virginia.

After suffering more than 12,000 casualties, Burnside called off the offensive and re-crossed the river. Lee’s reputation and his army’s morale soared with the decisive Confederate victory at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

On January 26, 1863, Lincoln replaced Burnside with Major General Joseph (“Fighting Joe”) Hooker in his quest to find a Union officer who could out-general Lee.

On April 27, Hooker led the Army of the Potomac back across the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers. He soon found one near Chancellorsville, Virginia on May 1. Outnumbering Lee’s army by a ratio of two to one, Hooker planned to use his numerical superiority to flank and entrap Lee’s army.

Lee anticipated Hooker’s plan, however, and boldly split his outnumbered army to check the Federal flanking movements.

After five days of intense fighting, Hooker withdrew his army from the field. Many consider the Battle of Chancellorsville to be the zenith of Lee’s military career. Once again he had fended off an advance by a much larger force, raising the already high morale of his army and prompting him to lobby for another invasion of the North.

While Lee was defeating Hooker at Chancellorsville, Major General Ulysses S. Grant was besieging the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi on the Mississippi River.

With Hooker’s army in retreat, many Confederate officials proposed sending some of Lee’s army west to relieve Vicksburg. Reluctant to reduce the number of troops protecting Virginia, Lee instead proposed another invasion of the North.

With his stature at an all-time high, Lee’s views prevailed, and Jefferson Davis authorized him to launch another offensive.

On June 3, 1863, Lee began moving portions of his army northwest toward the Blue Ridge Mountains. The Rebels crossed the mountains and moved north through the Shenandoah Valley, capturing the Union garrison at Winchester, Virginia, in the Second Battle of Winchester (June 13 to 15, 1863).

Lee’s army then began moving into Maryland and Pennsylvania. By that time, Hooker realized Lee’s movements and dispatched the Army of the Potomac to stop Lee’s advance.

As the Federals sought to locate Lee’s forces, Hooker engaged in a heated dispute with his superiors and rashly offered to resign as commander of the Army of the Potomac. President Lincoln quickly accepted the resignation, and on June 28, he replaced Hooker with Major General George Meade. Three days later, Meade’s army engaged Lee at the Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg.

From July 1 through July 3, the two armies fought the largest battle of the Civil War.

Meade’s army arrived at Gettysburg ahead of the Rebels and secured the high ground on the first day of battle. Seeing that the Federals held the better ground, some of Lee’s lieutenant commanders, particularly James Longstreet, advised Lee to move the Confederate army around Gettysburg and face Meade’s army on another day at a place of the Rebels’ choosing.

Fearing the effect that withdrawing might have on his army’s morale and, perhaps, placing too much stock in the seeming invincibility of the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee instead ordered ill-advised attacks against the Federal lines on the second and third days of the battle.

The results were catastrophic, particularly the assault on the Union center on July 3, which came to be known as Pickett’s Charge. As Lee watched the remnants of his army return from the failed assault on Cemetery Ridge, he acknowledged, “It is all my fault.”

That evening, the shattered Army of Northern Virginia began an arduous ten-day march back to Virginia, bringing Lee’s offensive to an ignominious end. Meade failed to pursue Lee as he withdrew, and for the remainder of the season, both armies were content to recuperate from the battle.

Meade’s failure to pursue Lee immediately after Gettysburg, coupled with his subsequent inaction in 1863, again prompted President Lincoln to find a general who would use the Union’s dominant resources to defeat the Confederacy.

On February 29, 1864, President Lincoln signed legislation restoring the rank of lieutenant general in the United States Army. On March 2, the president nominated Ulysses S. Grant, conqueror of Vicksburg and champion of Chattanooga, for the post.

Congress confirmed the nomination on the same day. On March 3, Lincoln summoned Grant to Washington. A week later, on March 10, the president issued an executive order appointing Grant as General-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States. On March 17, 1864, Grant issued General Orders, Number 12, taking command of the armies.

Grant immediately devised a plan to have all Union armies act in concert and then set his sights on defeating Lee. Making his headquarters with Meade’s Army of the Potomac, Grant launched his Overland Campaign in the spring, determined to go where Lee went.

Although it took nearly a year, Grant’s strategy eventually prevailed. Against the better-equipped and much larger Union army, Lee held his own at the bloody Battles of the Wilderness (May 5-7, 1864), Spotsylvania Court House (May 8-21, 1864), and Cold Harbor (May 31 – June 12, 1864), endured a prolonged Siege at Petersburg (June 9, 1864 – March 25, 1865).

By the end of 1864, the Confederacy’s military plight had become dire. Grant had Lee’s army bottled up in Petersburg and William T. Sherman captured Savannah on December 21 after making Georgia howl during his notorious March to the Sea.

As the situation worsened, Southerners began questioning President Jefferson Davis’s effectiveness as commander-in-chief. Opposition to Davis reached a crescendo on January 23, 1865, when the Confederation Congress enacted legislation creating the post of General-in-Chief of Confederate forces. A week later, the bedeviled president appointed Robert E. Lee to the post.

On February 6, the Confederate War Department issued General Orders, No. 3 announcing Lee’s appointment. On February 9, Lee issued his first general order as General-in-Chief announcing that he had assumed the post.

The change in leadership had little effect on the outcome of the war. In March 1865, Lee led his beleaguered forces in a desperate escape attempt that ended at Appomattox Court House. Finally, on April 9, 1865, Lee realized that the Army of Northern Virginia was vanquished, and he surrendered to Grant.

The Civil War lingered on for several weeks after the surrender at Appomattox Court House, but it was over for Lee. He returned to Richmond to reunite with his family.

On October 2, 1865, Lee was inaugurated as president of Washington University in Lexington, Virginia. On the same day, Lee signed an amnesty oath, swearing his allegiance to the Constitution and to the United States.

On December 25, 1868, President Andrew Johnson, issued a proclamation that unconditionally pardoned those who “directly or indirectly” rebelled against the United States. Johnson’s pardon ensured that Lee could not be charged with treason or insurrection.

Nevertheless, Lee’s citizenship was not restored during his lifetime. His citizenship was restored posthumously by an act of Congress, signed into law on August 5, 1975, by President Gerald Ford.

Lee served as president of Washington College until his death in 1870. During that time, he supported President Johnson’s Reconstruction plan and opposed the policies of so-called Radicals in Congress. He counseled compliance with federal authority but remained opposed to extending voting and civil rights to freed blacks.

On September 28, 1870, Lee suffered a stroke at his home in Lexington, Virginia. He died two weeks later on October 12. Lee’s remains were buried beneath the Lee Chapel on the campus of Washington University (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington.

Related Entries

- Ambrose Everett Burnside

- Ulysses S. Grant

- Overland Campaign

- Battle of Antietam

- Battle of Chancellorsville

- Peninsula Campaign

- Seven Days Battles

- George Brinton McClellan

- Abraham Lincoln

- Surrender at Appomattox Court House

- James Longstreet

- Jefferson Finis Davis

- George Gordon Meade

- Joseph Hooker

- Pickett’s Charge

- Battle of Cheat Mountain

- Joseph Eggleston Johnston

- Andrew Johnson

- Army of the Potomac (USA)

- Army of Virginia

- Mexican-American War

- General Orders, No. 13 (Virginia Forces)

- Special Orders, No. 22 (CSA)

- Message from Jefferson Davis Assigning Robert E. Lee to Command the Army of Northern Virginia

- General Orders, No. 14 (CSA)

- General Orders, No. 1 (Virginia Forces)

- Message from Robert E. Lee Assigning Joseph E. Johnston to Command of Troops in Carolinas

- Message from Joseph E. Johnston Regarding Robert E. Lee’s Order to Drive Back Sherman

- Army of Northern Virginia

- Message Announcing Robert E. Lee’s Confirmation as General-in-Chief of the Armies of the Confederacy

- General Orders, No. 3 (CSA)

- General Orders, No. 1 (CSA)

- John Brown