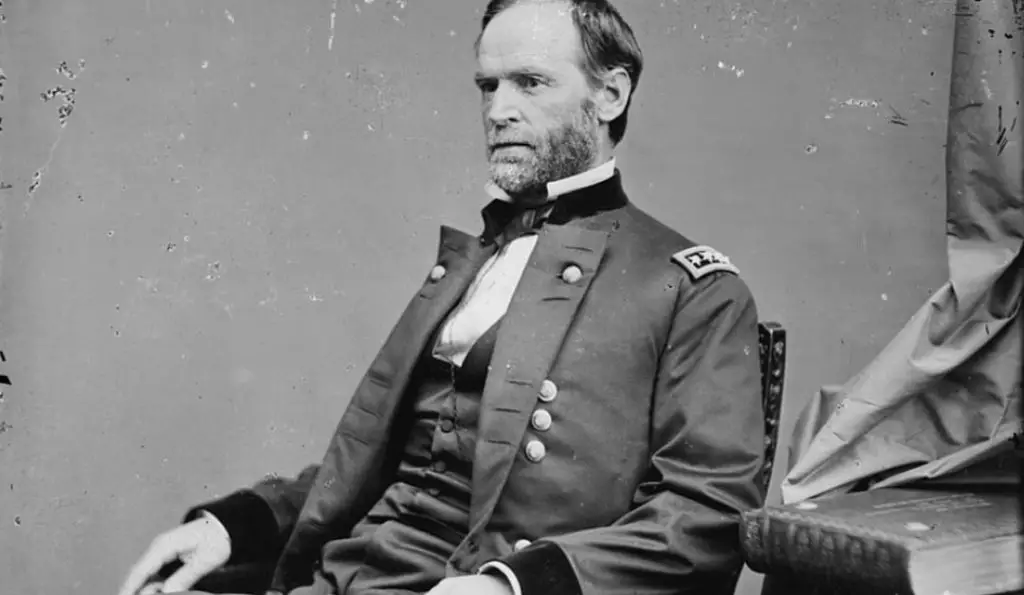

February 8, 1820–February 14, 1891

Celebrated in the North and reviled in the South, Ohioan William Tecumseh Sherman was a prominent Union general during the American Civil War. An accomplished soldier and able leader, Sherman is best remembered for warring against civilians during the Savannah and Carolina campaigns, which left a swath of destruction across the South during the latter part of the war.

William Tecumseh Sherman was born on February 8, 1820, in Lancaster, Ohio. He was one of eleven children of Ohio Supreme Court Justice Charles Robert Sherman and Mary Hoyt Sherman. Sherman’s father died unexpectedly in 1829, when Sherman was nine years old, and due to the family’s financial problems, he was sent to live with Lancaster resident Thomas Ewing, who was a prominent lawyer and Ohio politician. Ewing secured an appointment for Sherman to the United States Military Academy, and Sherman became a West Point cadet at the age of sixteen years, in 1836. Sherman graduated sixth in his class in 1840, and he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Third Artillery on July 1, of that year. Sherman saw action in the Second Seminole War in Florida (1835-1842) but was stationed in California during the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), thereby being deprived of the combat action that many of his contemporary officers experienced.

Sherman married Eleanor “Ellen” Boyle Ewing, the daughter of Thomas Ewing, on May 1, 1850, in a prominent wedding at the Blair House, in Washington, D.C. On September 27, 1850, he was promoted to the rank of captain. Dissatisfied with army life, Sherman resigned his commission on September 6, 1853, and he entered civilian life as a bank manager in San Francisco. After his bank failed, as a result of the Panic of 1857, Sherman briefly practiced law in Leavenworth, Kansas in 1858. In October 1859, he was appointed as the first superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning & Military Academy (later Louisiana State University). By all accounts, Sherman was an able administrator who was popular with the students and faculty. Nevertheless, he felt compelled to resign his position in January 1861, when he was required to receive and store arms surrendered by the United States Arsenal at Baton Rouge to the Louisiana Militia. For a few months in 1861, Sherman served as president of the St. Louis Railroad, a streetcar company in St. Louis, Missouri, before volunteering for military service at the outbreak of the American Civil War.

Sherman’s first commission during the Civil War was as a colonel of the 13th U.S. Infantry regiment, effective May 14, 1861. He was one of the few Union leaders who distinguished themselves at the First Battle of Bull Run (July 21, 1861), and on July 23, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln promoted him to brigadier general of volunteers, effective May 17, of that year. Sherman was then assigned to the Western Theater and replaced General Robert Anderson as commander of the Department of the Cumberland on October 8, 1861. On November 9, 1861, the Department of the Cumberland was reorganized as the Department of the Ohio, and General Don Carlos Buell replaced Sherman as department commander on November 15, at Sherman’s request. Sherman was then transferred to St. Louis, Missouri, serving under Major General Henry Halleck in the Department of the Missouri. While in St. Louis, Sherman underwent a personal crisis that prompted Halleck to judge him unfit for duty. Sherman went home to Lancaster to recuperate amidst rumors and stories in the press that he had gone insane. Despite the rumors, Sherman quickly recovered and was providing rear-area support for Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant’s capture of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in February 1862.

On March 1, 1862, Sherman was given command of the 5th Division of Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of West Tennessee (later the Army of the Tennessee). On the morning of April 6, his division bore the brunt of a surprise attack by the Confederate Army of the Mississippi on the first day of the Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7, 1862). As the battle raged, Sherman distinguished himself by preventing a Union rout and by helping Ulysses S. Grant plan and execute a successful counterattack on April 7. Despite winning the battle, both generals were heavily criticized for failing to construct adequate defensive fortifications and for ignoring or discounting intelligence reports regarding Confederate troop concentrations in the area. Major General Henry W. Halleck, Federal commander in the Western Theater, relieved Grant of his command, but Sherman remained in the field and assisted Halleck in capturing the Rebel stronghold at Corinth, Mississippi, on May 30, 1862 after a thirty-day siege.

In July 1862, the fortunes of Grant and Sherman improved when Halleck was promoted to General-in-Chief of the army and moved to Washington. Grant assumed command of the Army of the Tennessee, and Sherman became his most trusted subordinate. After assuming command, Grant turned his focus to capturing Vicksburg, Mississippi, the Gibraltar of the Confederacy. In late December 1862, Grant sent three divisions under Sherman to attempt an assault on Vicksburg from the northeast. The Federals proved no match for the Confederate defenders, and Sherman was dealt a devastating defeat at the Battle of Chickasaw Bluff (December 26-29, 1862), suffering over 1,100 casualties, compared to fewer than 200 for the Rebels. Following the repulse at Chickasaw Bluff, Major General John A. McClernand superseded Sherman in command of Grant’s forces north of Vicksburg. Although neither Grant nor Sherman liked the arrangement, Sherman redeemed himself by performing well during McClernand’s assault on Arkansas Post (January 9-11, 1863). By June, Grant found sufficient reason to relieve McClernand of his command and restore Sherman as his number-one subordinate. Although Sherman privately expressed reservations about Grant’s unorthodox strategy during the Vicksburg Campaign, he served Grant dutifully throughout the remainder of the successful operation.

On October 16, 1863, the War Department issued General Orders, No. 337 consolidating the Departments of the Ohio, the Cumberland, and the Tennessee under Grant’s command. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton directed Grant to move as quickly as possible to Chattanooga, Tennessee to assist the Army of the Cumberland, which was under siege by General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. Grant quickly ordered Sherman to transport the Army of the Tennessee from Mississippi to Chattanooga to reinforce the Army of the Cumberland. Grant arrived at Chattanooga on October 23, established a new supply route into the city, and began making preparations for a Federal breakout. Sherman followed with roughly 20,000 soldiers, who began entering Chattanooga on November 20. On November 23, about 14,000 Federal soldiers overran 600 Confederate defenders of a hill between Chattanooga and Seminary Ridge, known as Orchard Knob. The Union soldiers fortified the hill, which served as Grant’s headquarters for the remainder of the breakout. The next day, about 10,000 Union forces commanded by Major General Joseph Hooker captured Lookout Mountain, which overlooks Chattanooga. On the same day, Sherman moved three divisions across the Tennessee River and captured a position called Goat Hill near the Confederate lines on Missionary Ridge. On November 25, Grant ordered Sherman to advance on Missionary Ridge from the north and Hooker from the south. Sherman and Hooker launched their assaults early in the morning but made little headway by afternoon. Seeing their lack of progress, Grant ordered Major General George H. Thomas to lead the Army of the Cumberland in an assault on the Confederate center. The assault was initially successful, but Thomas’s men were eventually tied down by rifle and artillery fire from above them on the ridge. Still stinging from their embarrassing defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga in September, the Army of the Cumberland mounted a second heroic charge up the ridge and overran the Rebels. By 6 o’clock, the center of Bragg’s army was in full retreat and the Union held Missionary Ridge. After abandoning Missionary Ridge, Bragg ordered his army to march south toward Dalton, Georgia. Sherman and Hooker pursued briefly, but Grant soon called a halt, not wanting his forces to get too far from their supply lines.

Following the breakout from Chattanooga, Grant ordered Sherman north on November 29, 1863, to relieve Major General Ambrose E. Burnside’s Army of the Ohio, which was being besieged by Confederate General James Longstreet at Knoxville, Tennessee. As Sherman’s army approached Knoxville, Longstreet abandoned his investment and retreated toward Virginia, leaving Tennessee firmly under Union control.

After helping drive Longstreet away from Knoxville, Sherman returned to Ohio where he spent Christmas with his family. In February 1864, he traveled to Vicksburg where he initiated a campaign against General Leonidas Polk’s troops at Meridian, Mississippi. As Sherman approached Meridian, Polk determined that he could not stop the Federals, so he evacuated the city. Sherman reached Meridian on February 14 and began laying waste to the area, practicing the “total war” strategy that he would employ on his March to the Sea in November and December.

On March 3, 1864, President Lincoln ordered Grant to Washington, where he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general and commissioned as General-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States. Grant appointed Sherman to succeed him as commander of the Military District of the Mississippi, which encompassed all Union troops in the Western Theater. Grant’s primary military strategy was a coordinated effort to attack and defeat the two main Confederate armies in the field, Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in the east, and Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee in the west. On May 5, 1864, Grant launched his Overland Campaign against Lee in Virginia. Two days later, Sherman initiated his Atlanta Campaign, leading three armies out of Tennessee in pursuit of Johnston’s army. For the next four months, Sherman employed a series of flanking maneuvers to gradually drive the Army of Tennessee south toward Atlanta, Georgia. On August 12, 1864, Sherman was promoted to the rank of major general in the regular army. By September 1, the Confederate army (now commanded by General John Bell Hood) was in danger of being trapped in Atlanta and evacuated the city. On September 2, Sherman’s forces took possession of Atlanta. Although Hood’s army escaped, the capture of the Georgia capital was significant because it helped ensure President Lincoln’s reelection in November.

Sherman occupied Atlanta for the next two and one-half months. During that time, he convinced Lincoln and Grant to allow him to embark on a daring operation, dispatching part of his forces in pursuit of Hood’s army, while Sherman personally led an invasion force across Georgia toward the coastal city of Savannah. Sherman’s intent was to “make Georgia howl” by living off the land and destroying the property of Georgia civilians. Sherman argued that his operation would demoralize the South, thus ending the war sooner and ultimately saving lives. Although Lincoln and Grant had reservations about Sherman isolating his army by cutting communication and supply lines, they approved the plan. Before evacuating Atlanta, Sherman ordered “the destruction in Atlanta of all depots, car-houses, shops, factories, foundries.” After stripping the city of all materials that could be utilized by the South, the designated destruction began on November 12. Unfortunately, before Sherman’s army evacuated the city, Union soldiers engaged in unsanctioned arson, torching private residences and much of the downtown.

Sherman left Atlanta on November 15, 1864. For the next five weeks, his army cut a swath of destruction across Georgia. Although looting was prohibited, foraging parties were authorized “to gather turnips, apples, and other vegetables, and to drive in stock of their camp.” Sherman further instructed his foragers, who came to be known as “bummers” in the South, that “In districts and neighborhoods where the army is unmolested no destruction of such property should be permitted; but should guerrillas or bushwhackers molest our march, or should the inhabitants burn bridges, obstruct roads, or otherwise manifest local hostility, then army commanders should order and enforce a devastation more or less apples.” Northern soldiers took mules, horses and wagons that might aid the Union advance. Finally, Sherman instructed that “Negroes who are able-bodied and can be of service to the several columns may be taken along, but each army commander will bear in mind that the question of supplies is a very important one and that his first duty is to see to them who bear arms. …”.

Sherman met very little resistance from the rapidly depleting Confederate Army during his “March to the Sea.” He captured Savannah on December 21, and he telegraphed President Lincoln, “I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty guns and plenty of ammunition, also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton.”;

When the Savannah Campaign ended, Grant and Sherman decided that Sherman should move north and help Grant defeat Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Rather than move his army by steamer, Sherman persuaded Grant to let him march north through the Carolinas, exercising his anti-civilian practices along the way. His soldiers were especially destructive in South Carolina, the first state to secede from the Union. Federal forces captured Columbia, the state capital, on February 17, 1865, and fires that night destroyed most of the central city. The source of the conflagration remains controversial to this day. Some, including Sherman, claimed that Southern soldiers started the blaze by burning bales of cotton as they retreated from the city; some claimed that the fires were deliberate acts of vengeance by Yankee soldiers; while still others claimed that the source was accidental. Whatever the truth, the burning of Columbia has contributed to Sherman’s status in the South as the most detested of Union generals.

After destroying anything of military value in Columbia, Sherman continued his march north, meeting little resistance other than Southern cavalry attacks until reaching Bentonville, North Carolina on March 19, 1865. There, his army was attacked by forces commanded by a “who’s who” of Confederate leaders, including Joseph E. Johnston, P.G.T. Beauregard, Braxton Bragg, William J. Hardee, and D.H. Hill. The first day of the Battle of Bentonville (March 19-21, 1865) went well for the Confederates, but on the next day, the second wing of Sherman’s army arrived on the scene, forcing a Rebel retreat.

After another month of skirmishing, Johnston realized that his position was hopeless when Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Grant on April 9, 1865. Johnston persuaded Confederate President Jefferson Davis to allow Johnston to enter into negotiations with Sherman to surrender the last major Rebel force in the field. Davis agreed, if Johnston could get Sherman to agree to terms more generous than those offered to Lee at Appomattox Court House. Specifically, Davis sought a surrender that restored the political rights and privileges of Southerners. Although Sherman was not authorized to negotiate political terms, he acceded to Johnston’s request when the two met at Bennett Place, in North Carolina, on April 17. Sherman believed that the terms he offered were consistent with President Lincoln’s stance of seeking “malice toward none, with charity for all.” Further, he feared that not acquiescing to Davis’s conditions might compel Johnston to halt the negotiations and continue the war. On April 18, the two generals signed terms of surrender that were agreeable to Davis. Northern leaders, however, were in no mood for reconciliation, especially because President Lincoln had been assassinated on April 14. Grant was dispatched to North Carolina, where he met with Sherman and ordered him to negotiate new terms of a military nature only. Sherman and Johnston met again at Bennett Place on April 26, and terms similar to those offered at Appomattox Court House were agreed upon.

When the war ended, Sherman remained in the regular army and was assigned to command the Military Division of the Mississippi and later the Military Division of the Missouri, encompassing all lands west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains. On July 25, 1866, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general. When Grant became President of the United States in 1869, Sherman was promoted to Commanding General of the United States Army. His main duties in the West included subjugating hostile Native American tribes, protecting settlers, and safeguarding the extension of railroads. His treatment of natives who resisted Federal authority was kindred to his actions against Southerners who contested his advances through Georgia and the Carolinas. As was the case during the latter part of the Civil War, Sherman believed that the most efficient way to subjugate hostile native tribes was to destroy the resources that enabled them to sustain their resistance.

Sherman resigned as commanding General of the Army on November 1, 1883, and he retired from the army on April 8, 1884. The same year, Republicans began promoting him as a possible candidate for the presidency. Sherman, however, had no political ambitions. He quashed any discussion of his selection by tersely stating, “I will not accept if nominated and will not serve if elected.”

Sherman spent the latter part of his life enjoying New York society and speaking at dinners, banquets and Civil War veterans’ reunions. William Tecumseh Sherman died at New York City on February 14, 1891, of unspecified causes. Following a funeral at his home on February 19, Sherman’s body was transported to St. Louis, Missouri, where his son Thomas Ewing Sherman, a Jesuit priest, presided over a second funeral on February 21. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston served as a pallbearer at the New York funeral. Sherman is buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis.

Related Entries

- Ambrose Everett Burnside

- Battle of Chickamauga

- Henry Wager Halleck

- John Bell Hood

- Vicksburg Campaign

- Braxton Bragg

- Overland Campaign

- Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard

- Ulysses S. Grant

- Don Carlos Buell

- Edwin McMasters Stanton

- General Orders, No. 337 (U.S. War Department)

- Robert Edward Lee

- Battle of Chattanooga

- George Henry Thomas

- James Longstreet

- Battle of Fort Donelson

- Battle of Fort Henry

- Jefferson Finis Davis

- Battle of Shiloh

- Battle of Corinth II

- Joseph Hooker

- Battle of Dalton I

- Battle of Bentonville

- Joseph Eggleston Johnston

- Army of the Ohio 1861?1862

- Department of the Ohio

- General Orders, No. 1 (Division of the Mississippi, 1864)

- General Orders, No. 98 (U.S. War Department)

- Special Field Orders, No. 44 (Division of the Mississippi)

- Army of the Tennessee

- Army of the Cumberland

- Sherman’s March to the Sea

- Robert Anderson

- Leonidas Polk

- General Orders, No. 210 (U.S. War Department)

- General Orders, No. 349 (U.S. War Department)

- General Orders, No. 68 (U.S. War Department)

- General Orders, No. 256 (U.S. War Department)

- General Orders, No. 3 (U.S. War Department)

- President Lincoln’s Executive Order Tendering Thanks to William T. Sherman

- Mexican-American War

- Army of Northern Virginia

- Abraham Lincoln

- Army of the Mississippi (CSA)

- Siege of Corinth

- John Alexander McClernand

- Chattanooga Campaign

- Battle of Missionary Ridge

- Army of the Ohio 1863?1865

- Battle of Meridian

- Atlanta Campaign

- Battle of Atlanta

- William Joseph Hardee

- Surrender at Appomattox Court House

- Surrender at Bennett Place

- Daniel Harvey Hill