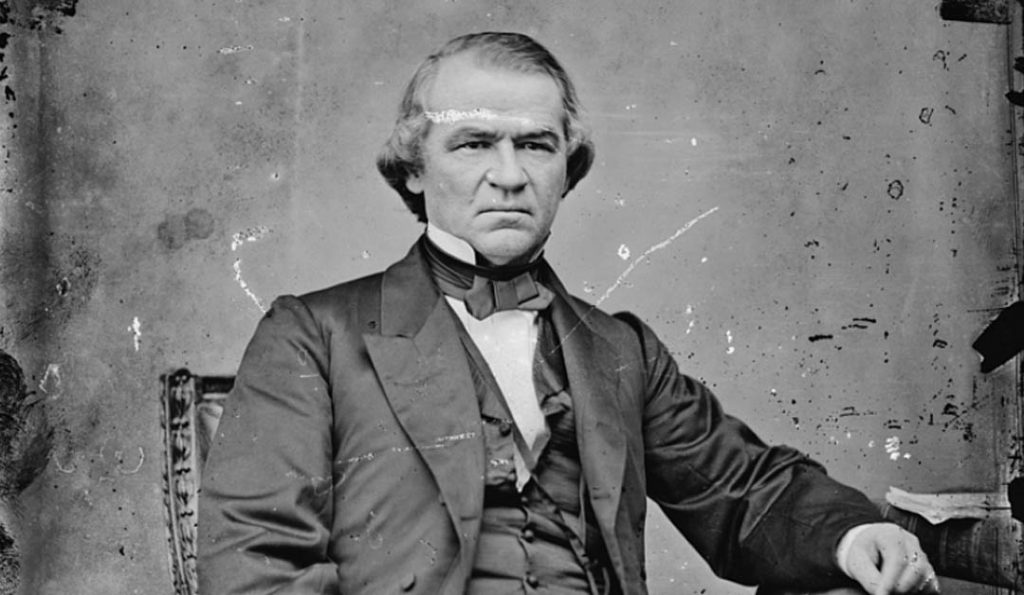

December 29, 1808 – July 31, 1875

Born into poverty, Andrew Johnson rose to become the seventeenth President of the United States in 1865. Although acquitted in his trial before the U.S. Senate, Johnson remains one of only two presidents ever impeached by the House of Representatives.

Andrew Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina on December 29, 1808. He was the youngest of two sons born to Jacob and Mary (“Polly”) McDonough Johnson. Johnson’s father died in 1812, leaving the family destitute. Johnson never attended school, and in 1818, his mother apprenticed both of her sons to a local tailor. During his apprenticeship, Johnson learned the alphabet and acquired rudimentary reading skills. He also became skilled in a gainful trade, but he chafed at the apprenticeship arrangement. In 1824, Johnson slipped away to nearby Carthage, where he found employment as a journeyman tailor for several months. Fearing that he would be captured and returned to Raleigh, Johnson then moved to Laurens Court House, South Carolina, where he worked as a tailor for two years. In 1826 Johnson briefly returned to Raleigh, long enough to convince his mother and stepfather, Turner Daugherty, to move west to Tennessee.

Johnson settled in Greeneville, Tennessee in 1826, where he eventually opened his own tailoring business. One year later, on May 17, 1827, he married sixteen-year-old Eliza McCardle. His wife, who was better educated, taught Johnson arithmetic and improved his reading and writing skills. Mrs. Johnson remained devoted to her husband throughout their fifty-year-long marriage that produced five children. Afflicted with tuberculosis sometime during the 1850s, she seldom participated in affairs of state throughout her husband’s long political career.

As Johnson’s tailoring business began to flourish, he became active in local politics. A Jacksonian Democrat, Johnson favored states’ rights and limited federal government. He championed the common folk, but opposed abolition. In 1829, Greeneville residents elected Johnson as a town alderman. Five years later, they elected him as their mayor at age twenty-six. In 1835, Johnson became a member of the Tennessee state legislature. He lost his re-election bid in 1837, but voters returned him to the legislature in 1839. One year later, Tennessee voters elected Johnson to the state senate, where he served from 1841 to 1843.

In 1842, the voters of Tennessee’s First Congressional District elected Johnson to the United States House of Representatives. That same year, Johnson bought his first slave, a fourteen-year-old girl named Dolly. He eventually owned as many as eight slaves. Elected to the House a total of five times, Johnson served in the Twenty-eighth through Thirty-second Congresses from March 4, 1843 to March 3, 1853. During his tenure in Congress, Johnson introduced an unsuccessful homestead bill aimed at providing free farmland to poor citizens.

Johnson chose not to run for reelection to the House in 1852, because gerrymandering by the Whig-dominated state legislature left him little chance for victory. Instead, he ran a successful campaign for governor of Tennessee. Reelected in 1854, Johnson served as governor for four years, until the Tennessee legislature selected him to join the United States Senate in 1857.

Soon after taking his seat in the Senate, Johnson reintroduced his Homestead Bill. Two years later, both houses of Congress approved the bill, but President James Buchanan vetoed it. During his tenure in the Senate, Johnson was a Southern moderate. He defended slavery and reviled abolitionists, but he opposed secessionists and staunchly defended the sanctity of the Union.

As states began seceding from the Union following the election of President Abraham Lincoln, Southern senators and representatives voluntarily relinquished their seats in Congress. When Tennessee seceded on June 8, 1861, Johnson sided with the Union and became the only Southern Senator to retain his seat in Congress. Southerners denounced Johnson as a traitor, confiscated his home in Tennessee, and drove his family from the state. When Federal troops gained control of Tennessee in 1862, Johnson resigned his seat in the Senate to accept President Lincoln’s appointment as Military Governor of Tennessee.

Johnson’s loyalty to the Union earned a great deal of notoriety and respect in the North. As the election of 1864 approached, President Lincoln’s reelection seemed far from a certainty. The necessities of war prompted Republicans and loyal War Democrats to bond and to form a new coalition called the National Union Party. When the party held its national convention at Baltimore in June 1864, it was a foregone conclusion that Lincoln would be nominated for a second term. Seeking to balance the ticket, delegates selected Johnson–a Southerner and a Democrat as Lincoln’s running- mate on the first vice-presidential ballot. Following their landslide victory in November, Lincoln and Johnson were inaugurated on March 4, 1865. Johnson served only forty-two days as Vice President before becoming the seventeenth President of the United States on April 15 due to Lincoln’s assassination.

Eleven days after Johnson assumed the presidency, Joseph E. Johnston surrendered the last major Confederate army in the field to William T. Sherman at Bennett Place, North Carolina, effectively ending major organized combat in the American Civil War. With Congress in recess, Johnson turned his attention to reconstructing the Union, implementing the lenient approach that Lincoln favored. Like Lincoln, Johnson believed that the Southern states had never legally left the Union. Thus, Reconstruction was a matter of forming new state governments in the South so that they could resume their constitutionally-guaranteed status, including representation in Congress. To that end, Johnson implemented a modified version of Lincoln’s 1863 Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, offering amnesty to nearly all Southerners willing to swear an oath of allegiance to the Union. Johnson’s amnesty plan excluded Confederate officials and Southerners who owned taxable property in excess of twenty thousand dollars; however, those people were eligible to receive presidential pardons on an individual basis. Johnson’s plan also returned property confiscated during the war to white Southerners. Hoping to end Reconstruction before Congress reconvened in December, Johnson appointed temporary governors in the Southern states to oversee the drafting of new state constitutions, and he agreed to recognize officially each state that complied with constitutional requirements for statehood and that ratified the Thirteenth Amendment.

Congress had other ideas. By the time the legislature reconvened in December 1865, Johnson considered the Union reconstructed. Although the Southern states reluctantly accepted emancipation, the newly-formed state governments quickly began enacting “Black Codes,” severely restricting the civil rights of African Americans. Angered by Southern treatment of former slaves, which increasingly involved violence, as well as by Johnson’s attempt to impose his own version of Reconstruction, Congress refused to seat representatives from the Southern states. Dominated by Northern Republicans, Congress proceeded to enact its own version of Reconstruction through a series of acts and proposed constitutional amendments. The Congressional version of Reconstruction established federally ensured rights for former slaves and imposed much harsher treatment of Southern states, including military occupation. Congress passed much of its Reconstruction legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Second Freedmen’s Bureau Act, and Military Reconstruction Acts of 1867, over President Johnson’s vetoes, setting up a showdown between the two branches of government.

As the 1866 off-year elections approached, Johnson attempted to end his growing impasse with Congress by going on a speaking tour through the Midwest with the dual purpose of generating support for his Reconstruction policies and encouraging voters to elect Democratic representatives more sympathetic to his own views. Known as the “Swing Around the Circle,” the trek turned into a mudslinging campaign between Johnson and Radical Republicans, with disastrous results for the President. Not only did he alienate the few supporters he had in Congress, but the electorate responded by sending even more hardline Republican reconstructionists to Washington.

The confrontation between Congress and the President reached a crisis in February 1868, when Johnson attempted to remove Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton from his cabinet, in violation of the Tenure of Office Act, which Congress passed in 1867 over Johnson’s veto. That act, which the Supreme Court later ruled unconstitutional, prevented the President from removing from office any Federal official whom the Senate had confirmed. Prompted by Johnson’s flagrant challenge to Congressional authority, the House of Representatives voted to impeach the President on February 24. The House brought eleven charges against Johnson in his trial before the Senate, which began on March 30, 1868. After six weeks of hearing evidence against the President, the Senate voted for acquittal on the eleventh article on May 16. Although a plurality of Senators (thirty-five to nineteen) found Johnson guilty, the total was one vote short of the constitutionally required two-thirds majority to remove the President from office. On May 26, the Senate voted on the second and third articles with the same results. With no prospects for conviction on the remaining charges, the trial ended.

Following his acquittal, Johnson served the last ten months of his presidency still at loggerheads with Congress. At the 1868 Democratic National Convention, party delegates nominated Horatio Seymour as their presidential candidate over the incumbent Johnson. On March 4, 1869, Johnson completed his term as president and returned to Greeneville, Tennessee.

Johnson’s political career did not end when his presidency expired. In 1872, he made an unsuccessful bid to be elected to the United States House of Representatives. In January 1875, the Tennessee legislature elected Johnson to a seat in the United States Senate, making him the only former president to sit later as a senator. Johnson served in the Senate from March 4, 1875 until his death a few months later.

Johnson suffered a stroke on July 28, 1875, while visiting his daughter, Mary, near Elizabethton, Tennessee. He died three days later on July 31, 1875. At his request, Johnson was wrapped in an American flag and buried with a copy of the Constitution. Interment was on his family estate outside of Greeneville, Tennessee. Johnson’s daughter, Margaret, later willed the property to the U.S. government. In 1906, Congress designated the site as the Andrew Johnson National Cemetery.

Related Entries

- William Wing Loring

- Union Party

- William Tecumseh Sherman

- Abraham Lincoln

- Joseph Eggleston Johnston

- Civil Rights Act of 1866

- Reconstruction Acts

- General Orders, No. 67 (U.S. Department of War)

- Presidential Proclamation 153

- Presidential Proclamation 157

- Presidential Proclamation 148

- Presidential Proclamation 134

- Surrender at Bennett Place