May 31–June 12, 1864

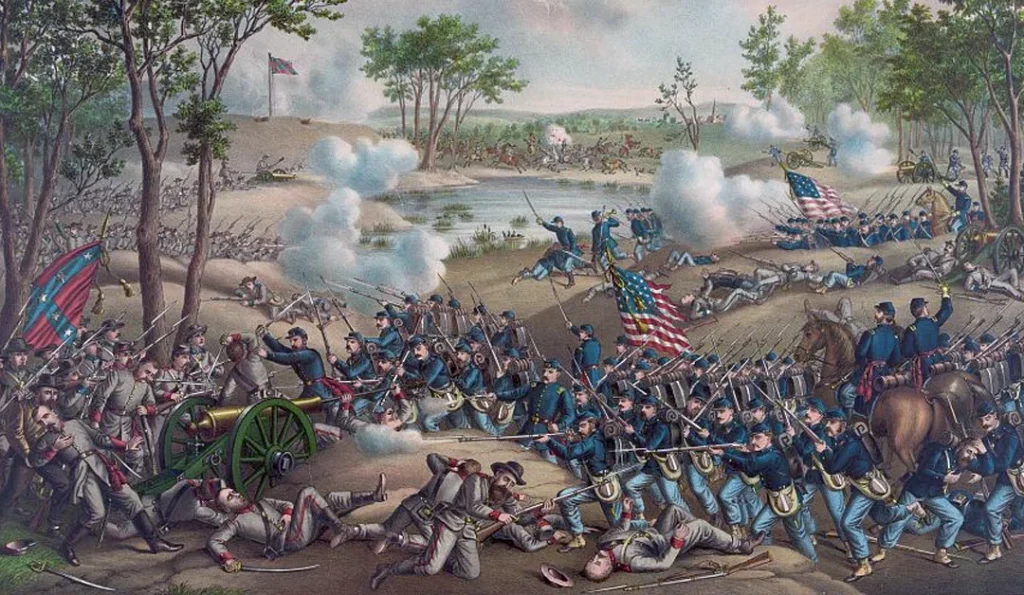

The Battle of Cold Harbor was the last major battle in Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign. Between May 31 and June 12, 1864, the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Major General George Meade, engaged the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee, at a strategic crossroads east of Richmond, known as Cold Harbor. The battle is most remembered for an ill-advised and poorly planned Union assault on Rebel lines on the morning of June 3.

On March 10, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Ulysses S. Grant as General-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States. Grant brought with him, from his successes in the western theater of the war, a reputation for the doggedness Lincoln was seeking. Unlike previous Union generals, whose leadership was marked their own timidity, Grant was tenacious. Upon his arrival in Washington, Grant drafted a plan to get the various Union armies in the field to act in concert. He also devised his Overland Campaign to invade east-central Virginia. Unlike previous campaigns into that area, Grant’s focused on defeating Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, rather than capturing or occupying geographic locations. Grant instructed General George Meade, who commanded the Army of the Potomac, “Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.” Grant realized that with the superior resources he had at his disposal, Lee was destined to lose a war of attrition, as long he was persistently engaged.

On May 4, 1864, Grant launched the Overland Campaign, when the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers. Although Meade nominally commanded the Army of the Potomac, as General-in-Chief of the Armies, Grant chose to accompany the army in the field so that he could personally supervise overall campaign operations.

Throughout the month of May, the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia slugged it out in a series of battles including the Wilderness (May 5-7), Spotsylvania Court House (May 8-21), North Anna (May 23-26), and Totopotomoy Creek (May 29-30). Although the Rebels inflicted high casualties on the Federals during those battles, Grant continued his strategy of moving south and east to Lee’s right, and then re-engaging. Grant’s moves forced Lee to reposition his lines continually to defend Richmond.

Following Totopotomoy Creek, Grant discovered that Lee had moved a portion of his army past the Federal left flank to a strategic crossroads called Old Cold Harbor. Grant suspected that Lee was attempting to prevent the flow of Union supplies and possible reinforcements from arriving via the James River. On May 31, General Philip Sheridan’s Union cavalry seized the vital crossroads at Cold Harbor from the Confederates. When Rebel reinforcements arrived, Sheridan withdrew. Realizing the importance of the position however, Grant ordered Sheridan to re-capture the crossing and to hold it at all costs. Grant then ordered Meade to begin sending infantry troops to reinforce Sheridan’s cavalry immediately. Wishing to re-take the crossing, Lee also began sending more troops to Cold Harbor.

On June 1, Sheridan easily repulsed a counterattack by Rebel infantry trying to recover the position. Later in the day, a Union attack temporarily broke Confederate lines, but a Rebel counterattack sealed the break and ended the fighting for the day.

Overconfident from the constant hammering that the Union army had inflicted upon the Rebels throughout the month, Grant now erroneously believed that Lee’s army was on the verge of collapsing. Thus, he ordered an all out frontal attack on the Confederate lines for the next morning. When his corps commanders reported that their troops were spent following the forced march to Cold Harbor, Grant approved delaying the assault until the morning of June 3. The delay was critical, enabling Lee to strengthen his defenses and to reinforce his army. For their part, the Federals failed to use the time to perform reconnaissance that might have disclosed the fate that awaited them.

At 4:30 a.m., on June 3, nearly 50,000 Union troops launched a massive assault on the Confederate line. In less than an hour, nearly 7,000 of them lay dead, wounded, or dying on the field of battle. Many others were pinned down by withering infantry and artillery fire, unable to advance or retreat. Their only option was to use whatever tools were available to dig makeshift trenches to shield themselves until darkness. At 12:30 p.m., Grant issued an order suspending the attack. Incredibly, he ordered another assault later in the day. While some units complied, other officers and soldiers flatly refused to obey the suicidal order.

The next four days constituted a period of unparalleled horror in the American Civil War. Thousands of wounded Union soldiers cried out in pain and suffering as Rebel sharpshooters prevented rescuers from rendering aid. Unwilling to acknowledge defeat, Grant refused to agree to a truce to attend to the wounded until June 7. By then, nearly all of the wounded had died.

For nine days following the fateful assault, the two armies continued to confront each other until Grant abandoned his strategy of attacking Lee’s army. On May 12, Grant evacuated Cold Harbor and moved Meade’s army across the James River to begin an assault on Petersburg, a crucial supply depot for Richmond and Lee’s army, which was located to the south of Richmond.

Ohio units that participated in the Battle of Cold Harbor included:

Infantry units:

- 4th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry

- 8th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry

- 60th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry

- 110th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry

- 122nd Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry

- 126th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry

Artillery units:

- Battery H, 1st Ohio Light Artillery Regiment

Cavalry units:

- 2nd Regiment Ohio Volunteer Cavalry

- 6th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Cavalry

Following the battle, Grant’s initial report to army chief-of-staff General Henry Halleck was blatantly fallacious. He reported, “Our loss was not severe, nor do I suppose the enemy to have lost heavily.” Halleck and other Washington leaders were probably not overly eager to discover the truth. Formal affirmation of such a disastrous defeat, along with the disturbing horror of its aftermath, may have done irreparable damage to President Lincoln’s re-election efforts. Years later, in his memoirs, Grant acknowledged that, “I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. I might say the same thing of the assault of the 22d of May, 1863, at Vicksburg. At Cold Harbor no advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained.”